Butt Shots in Camera Trapping: Causes and Fixes

We all put trail cameras up with hopes of capturing the perfectly framed face shot of a panther, or bobcat, or fox. With these great expectations, we download images from SD cards left months in the field, only to discover perfectly framed photos of the derrieres — the infamous “butt shot!”

The impression we have, on reviewing these photos, is that we have placed the camera poorly. “If only I had put the camera facing in the other direction!” But this, it turns out, is a case of sample bias — animals coming towards the camera are much less likely to appear in photos vs. animals walking away from the camera. So, we conclude based on the photos we see, that the animals are almost always walking away from the camera. To demonstrate this concept, I once set up a trail camera looking down our driveway. I found photo after photo of my own backside as I headed out on my morning run; yet, despite the fact that I always returned running back up the same driveway, there were zero photos of me on the way back.

How does a trail camera sense an animal?

To understand what’s going on, we have to look deeper into the way a trail camera detects a target and triggers the camera to take a photo. Most commercial trail cameras use a PIR or Passive InfraRed sensor, integrated into the camera unit, and looking out on the same scene as the camera. The sensor detects changes in light in the infrared portion of the electromagnetic spectrum at a wavelength of about 10 micrometers. This is exactly in the range of the peak radiation emitted by warm bodies at a temperatures near 37C (100F).

The term passive means that the sensor is detecting a change in the ambient conditions. In contrast, an active sensor might illuminate a scene with visible or infrared light and then detect the reflection of the light off of a target.

In many ways, PIR sensors are ideal sensors for trail cameras. Most animals of interest are warm blooded, and therefore “glow” in the infrared spectrum, day or night. A passive sensor can detect this glow using very little power vs. the high power required to illuminate the scene with an active sensor, and thus can be battery-powered yet still stay out in the field for months. Moreover, the PIR sensor is mounted right next to the camera, guaranteeing (or so it would seem) that an animal in the field of view of the sensor will also appear in the photo.

The Problem with PIR Sensors

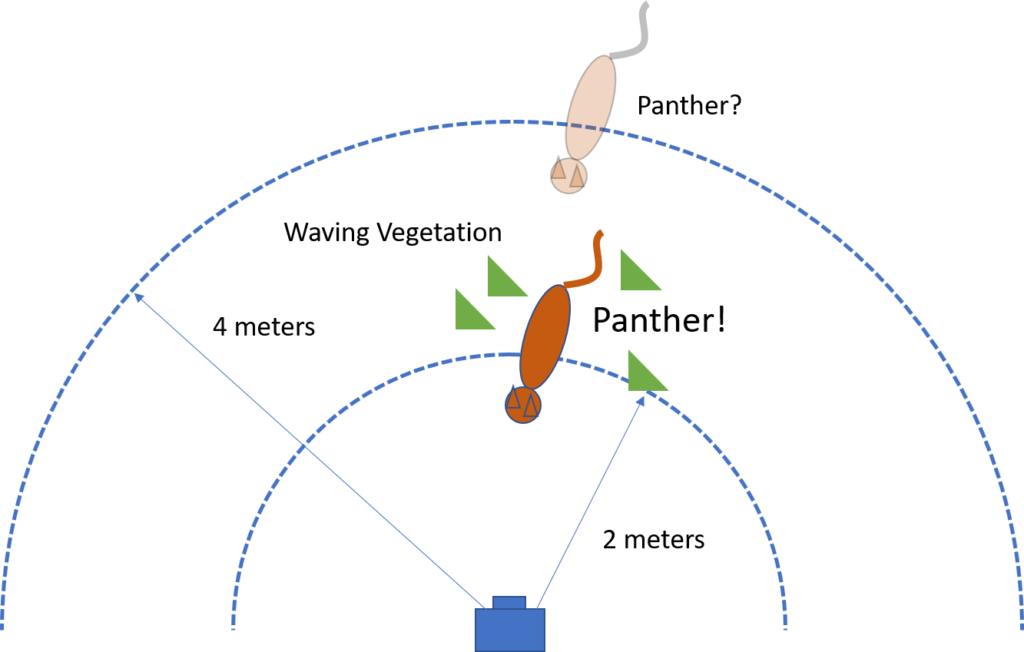

But as good as this arrangement is, it’s not perfect. The problem is fundamental to all light sensors — they are less sensitive as the target is further away. In fact, the sensitivity gets worse as the square of the distance to the target: the sensor detects a signal 1/4 as large for a target that is twice as far away; 1/16 as large for a target 4 times as far away, etc.

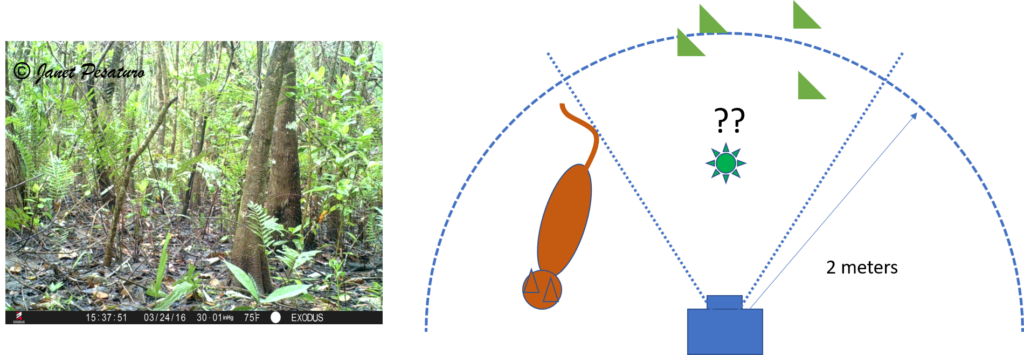

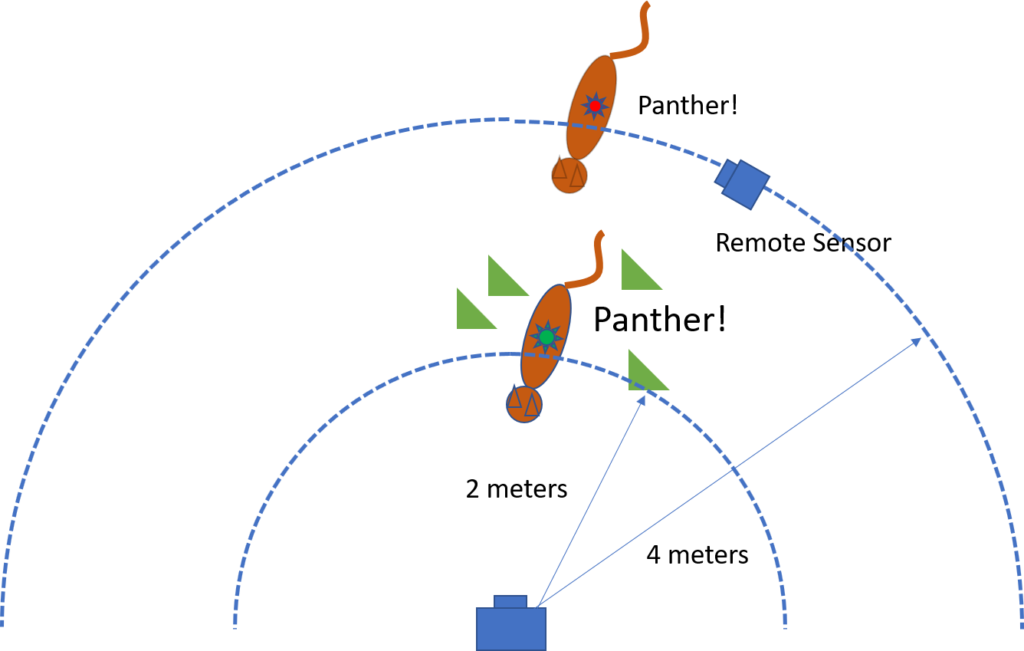

All sensor systems need to deal with noise. We know by experience that there are changes in the IR view in front of our cameras other than animals — like waving vegetation, shadows, etc. In practice, for a sensor to trigger a photo, the signal from the sensor must rise above some noise level. But since the signal itself for a “real” target gets smaller the further away it is, this means that the same animal that triggers the camera when it is 2 meters away, may not trigger the camera when it is 4 meters away.

Actually, it’s even worse than this. PIR sensors in trail cameras have other limitations, including those due to trade-offs made to reduce cost and power, to optimize for detecting certain species, etc. These are for another post. For those interested in these details, as well as in a field-test-based approach to evaluating trail camera trigger sensitivity featuring a canine helper, I highly recommend Peter Apps and John McNutt’s papers featured in the reference list.

Anatomy of a Bad Photo

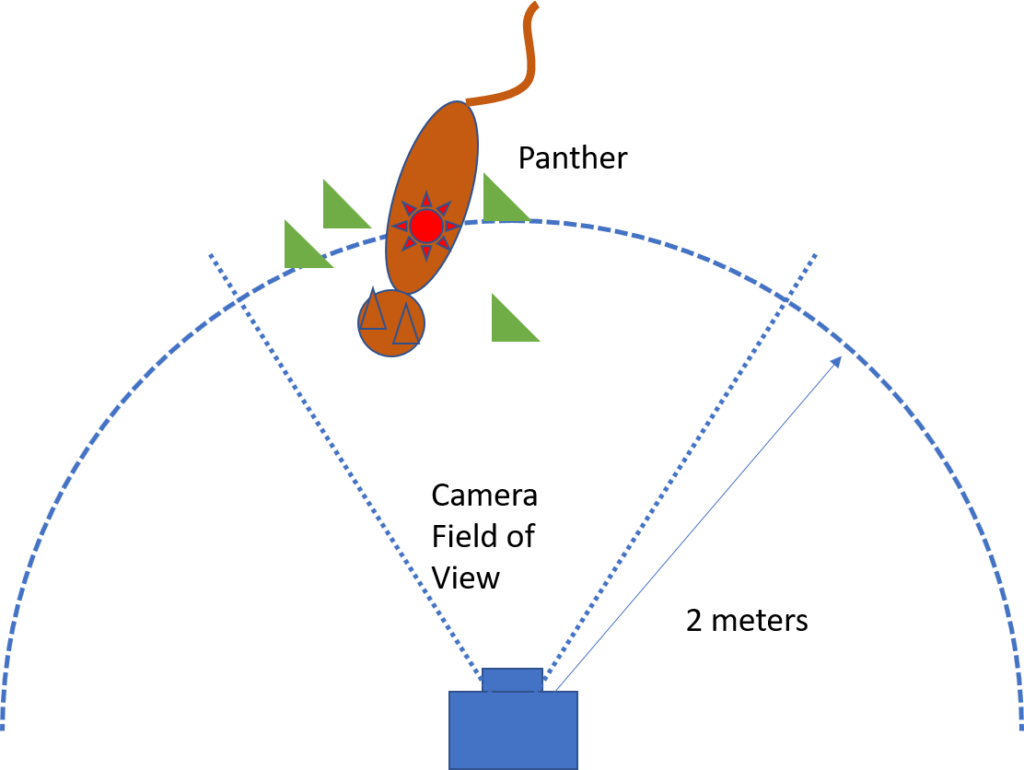

So, what does this have to do with butt shots? Everything, it turns out. Consider the following example: let’s say that we have a sensor that can detect a Florida Panther (Puma concolor coryi) walking by when it is 2 meters away or less, and the camera has a trigger speed of one second. Let’s say that our panther is walking at about 1 meter per second — a leisurely pace.

For a cat walking toward the camera, the PIR detector in our example detects the animal when it is two meters away. At this point, the panther is facing the camera as it comes towards it. The photo would be perfect! But our camera has a trigger delay of 1 second, so it doesn’t take the photo for another second. By this time, the cat is a meter further along, and just outside of the field of view of the camera. The camera snaps a picture, but the frame is empty.

With a slow moving predator, like a panther, or a bobcat, one occasionally gets face shots despite the odds. But with a typically faster animal, like a fisher, coyote, fox, or wolf, by the time the photo is taken, the animal is almost always gone.

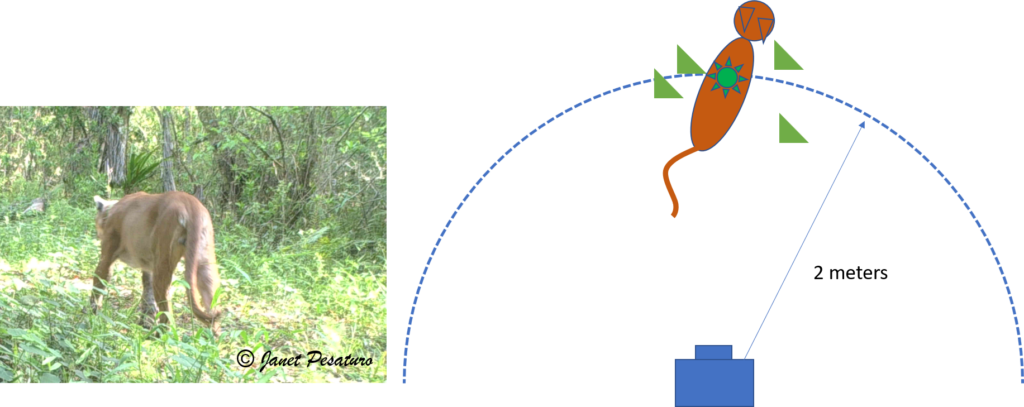

Contrast to this to the same animal walking away from the camera. In this case, the panther passes within a meter of the camera and triggers the sensor. A second later, when the photo is taken, the cat has walked another meter, and is now 2 meters from the camera — a perfectly composed photo! Except its walking away, so we capture another photo of a tail end.

Avoiding Butt Shots in Camera Trapping

Armed with this insight, what can we do to increase the odds of getting face shots? Certainly, we can buy a camera with a faster trigger speed, or a more sensitive detector, or we might simply select a higher sensitivity for the camera we have. But we’re working against physics here. A more sensitive detector may lead to more head shots of animals we want, but it will be more likely to trigger on noise — filling our SD cards with thousands of nuisance shots.

The easiest solution to this problem is to place the camera at locations where the animal is likely to slow down or stop. See some of our other posts for many of examples of clever camera placement, including at a:

- constriction (like a beaver dam) where the animal is likely to go often, but where it must proceed more slowly due to uneven footing.

- feature that might capture an animal’s attention. It is tempting (if not always effective) to “decorate” the landscape — perhaps with lures — to achieve this end, but there many of curious features that occur naturally, if one takes the point of view of the animal. For example, a marking or scenting area, or latrine. Of course, sometimes the camera itself becomes a curious object, leading to the ever popular “muzzle” or “dental” closeup.

- hunting area: A camera placed near a thorny thicket surrounded by rabbit scat might catch a slowly prowling predator looking into the prickly mess for dinner. Of course, you’ll likely get lots of photos or rabbits, too!

- obstruction in a trail that the animal must navigate, such as a fallen log, or rocky area.

A Remote Sensor

But are there other technical solutions to the problem of capturing face shots of an animal moving through the landscape? Yes, in principle. Let us now consider a remote trigger device. A PIR sensor (or other type of sensor) placed at a distance from the camera addresses the “sensitivity at a distance” problem. A moving animal can now be close enough to the remotely mounted sensor to be quickly detected, but far enough away from the camera to get a good photo.

In the earlier example of the panther moving towards the camera, if the same sensor had been placed 3 meters up the trail, we’d have gotten a nice face shot a second later, 2 meters from the camera. For a more detailed description of a such a setup suitable for backyard captures, see: What Is Lurking In Your Backyard?

Unfortunately, most standard trail cameras do not support remote sensors. There are options for some higher end commercial offerings (e.g. Cognisys Scout PIR Sensor ), and for homebrew hackers to place the sensor away from the camera. On the downside, we now have two things we need to set up: a camera, and a sensor. We also need some means (like a wire, or radio connection) between the remote sensor and the camera to trigger the camera when the remote sensor finds and animal. Finally, we have to guess correctly the likely path of the animal, and get our setup just right to match.

Perhaps some future trail cameras will make this easier and less expensive, but for all these reasons, Janet and I have not really used remote sensors in the field, relying more on wile and lots of camera hours for the coveted face shot. Have you tried remote sensors in your camera trapping work? What did you learn? Do you have any other thoughts about butt shots in camera trapping? Please comment below.

Sources

- Peter Apps, John Weldon McNutt, “Are camera traps fit for purpose? A rigorous, reproducible and realistic test of camera trap performance,” African Journal of Ecology, 2018.

- Peter Apps, John Weldon McNutt, “How camera traps work and how to work them,” African Journal of Ecology, 2018.

- Cognisys Scout PIR Sensor

The author of this post is Robert Zak – just pointing that out for regular readers who might have noticed the different writing style, but didn’t notice the different name at the top of the page. Bob and I have been camera trapping together for years, and I am thriled to have him begin contributing posts on tech topics. Look for more from him in the near future.

Once, as an experiment I think, or maybe because I lacked other places, I set two cameras of the same make, but different models together, one over the other. This at what was left of a road kill deer. One camera had many images of a red-tailed hawk, the other many images, but no red-tailed hawks.

Certainly I have those somewhere on my computer. If this every happens again I’ll do a better documentation job.

Cool blog. Of course, lots of butt shots. We all have them. This helps.

Thanks — I’m glad you found it useful. I’ve always consider any butt shot better than an empty card — at least we’re in the right place!

Also the angle of the camera across the view can have a great influence on trigger time. Even a small angle across the trail will greatly improve triggering when the animal is directly approaching. When a Butt Shot is captured it generally indicates an animal has suddenly appeared from behind the camera. The PIR sensor sees this sudden change in temperature in that edge area and triggers a photo. If an animal is walking directly toward the camera/sensor the temperature rise is much more gradual and will not trigger the PIR sensor until the animal approaches much nearer. Most sensors require a 5deg difference in background temperatures before they will trigger and with a slowly approaching animal this temperature difference tends to be filtered until the animal is much nearer. Most (if not all) companies test triggering distances by walking across the field of view of the camera and not directly toward it. This does not give a true test of the triggering filtering. Panasonic does make some security PIR lenses which are designed for motion directly approaching the sensor and I have built them into my remote triggers with success.

This is a really good point — and speaks to the other subtleties of the PIR sensor. I hope to cover this in a future post. Agree that the testing regimen of many trail cameras doesn’t cover all the uses we have in mind. I’m glad to hear of your success with the Panasonic sensor. And thanks for reading and commenting!

When Browning came out with their “Smart IR” feature that allows the camera to continue operation as long as the sensor detects a subject, I was inspired to write a note of appreciation to Browning. I added that the next evolution I would appreciate would be an accessory remote sensor. I had used wireless “driveway alert” sensors in a few locations around home to warn Us of animal activity with interesting and helpful success. It didn’t seem too far of a stretch to incorporated a similar option into the triggering of Our trail cams. I eventually got a vague form letter reply, but so far no remote sensor….not that I was holding My breath.

Great idea! 🙂 Hopefully Browning is not averse to accepting good ideas from their customers! (although I do know that corporate legal types worry about accepting third party intellectual property for fear of licensing issues). A potential technical issue with a remote sensor is power. For convenience, a wireless link between the remote sensor and the camera would be best. Not a problem for the sensor — it only needs to consume power transmitting when it detects an animal, which isn’t that often. The receiver, however, has to be on all the time, which can be power hungry. For example, the receiver we use in our homebrew flash setup goes through 2 AA Lithium cells in 2-3 weeks. Fortunately, the “Internet of Things” trend is driving new technology in this area, including receivers with ultra low power wireless “wakeup”. Maybe when this technology becomes widely available, trail camera vendors will start including in their systems.

Most commercial cams are already set Up with provision for external power, so that might help. I was trying to think of a way a remote sensor could emit something other than a radio signal that would trip the existing or modified sensor the cam already has / uses. Moultrie has made supplemental flashes that are triggered by the presence of light from another camera. My experiments with them were disappointing, and their stand-by power drain was unreasonable. Their tech. is several yrs old. Anyway, It raises the question of maybe the remote sensor /sender could trip the camera’s existing sensor with a laser pulse or ??? A unit would only have to operate at 75′ to be handy.

I was thinking along similar lines, for example an “IR repeater” — i.e. a remote detector that generated (a large) thermal signal that could be detected by the camera’s own PIR sensor. But generating heat quickly, that could reliably be picked up by the camera seemed a little daunting. The laser idea could work over distances, but I worry would require too much alignment in the field (not to mention possible retina damage to the photo subjects?). Which brought me back to radio. Something like the RFicientBasic (R) with a 3 uA standby current would do the job nicely. Not clear from the website whether this part available yet.