River Otter Latrines: Finding and Identifying Them

Some animals drop scat indiscriminately, some distribute it strategically along travel routes, and others, like the river otter (Lontra canadensis), have special sites for eliminating, called latrines. But river otter latrines are more than toilets. Interesting behaviors can be observed at otter latrines, which is why I like to target them with camera traps. To find them, you need to know where to look, and how to identify the scat and scent mounds that comprise the latrine. Where otters are common, their latrines are among the easiest of scent posts to find.

Along with photos of scat, scent mounds, and latrines, I have included videos of otters in action at different types of latrine sites. Hopefully all of this will help you develop a search image and envision where and how otters do their thing next time you’re out tracking.

Note: in this post I deal specifically with inland river otters. Coastal river otters are a bit different in their social behavior and while they do create latrines, I don’t have experience tracking or camera trapping them in that setting.

Location of River Otter Latrines

1. Proximity to water

Inland river otters use ponds, lakes, rivers and streams, and usually make their latrines close to the water along any of them. Occasionally they make them as much as a few hundred feet away from water, but I’ve seen that only on runs connecting bodies of water. In my experience these latrines are smaller and more temporary than those at pond edges, lake shores, and stream banks.

2. Land features and the beaver connection

Peninsulas, smaller points of land that stick out into the water, and isthmuses (strips of land between water bodies) are popular otter latrine sites. Where beavers are present, otters are highly attracted to beaver wetlands and their latrines are often near or on beaver bank lodges and dams. A bank lodge is probably a special case of “point of land”, and a beaver dam may be a special case of “isthmus”.

But the connection between otter latrines and beaver ponds is probably more than just topography. Beaver wetlands are wildlife hot spots and home to fish, crayfish, frogs, and other goodies that otters eat, and old bank lodges make good otter dens. A latrine may be on the beaver dam itself if the above-water portion is prominent, wide and smooth. Otherwise, the pond edge where a beaver dam meets the land is a very popular latrine location.

One study found that otter latrines are more common near large conifers and another found they’re likely to be found near rock formations. I haven’t notice those associations, but it’s worth keeping them in mind.

3. Distance from human activity

Low human activity is another factor. The few I’ve seen near human trails were small and temporary. Fellow trackers have told me they’ve noticed long-used otter latrines disappear after human activity on a nearby trail increased.

Latrine Contents

1. Otter Scat

Otter scat is quite variable in appearance, ranging from well-formed tubular pieces to pudding-like plops to liquid splats. Given the otters diet of mostly fish and crayfish, the scat almost always contains fish scales, fragments of crayfish exoskeleton, or both. However, when the scat is fresh and moist, it may be difficult to see the contents without picking it apart. Eventually it dries into a pile of fish scales or crayfish parts….unless, of course, the otter has been feeding on scale-less fish or frogs.

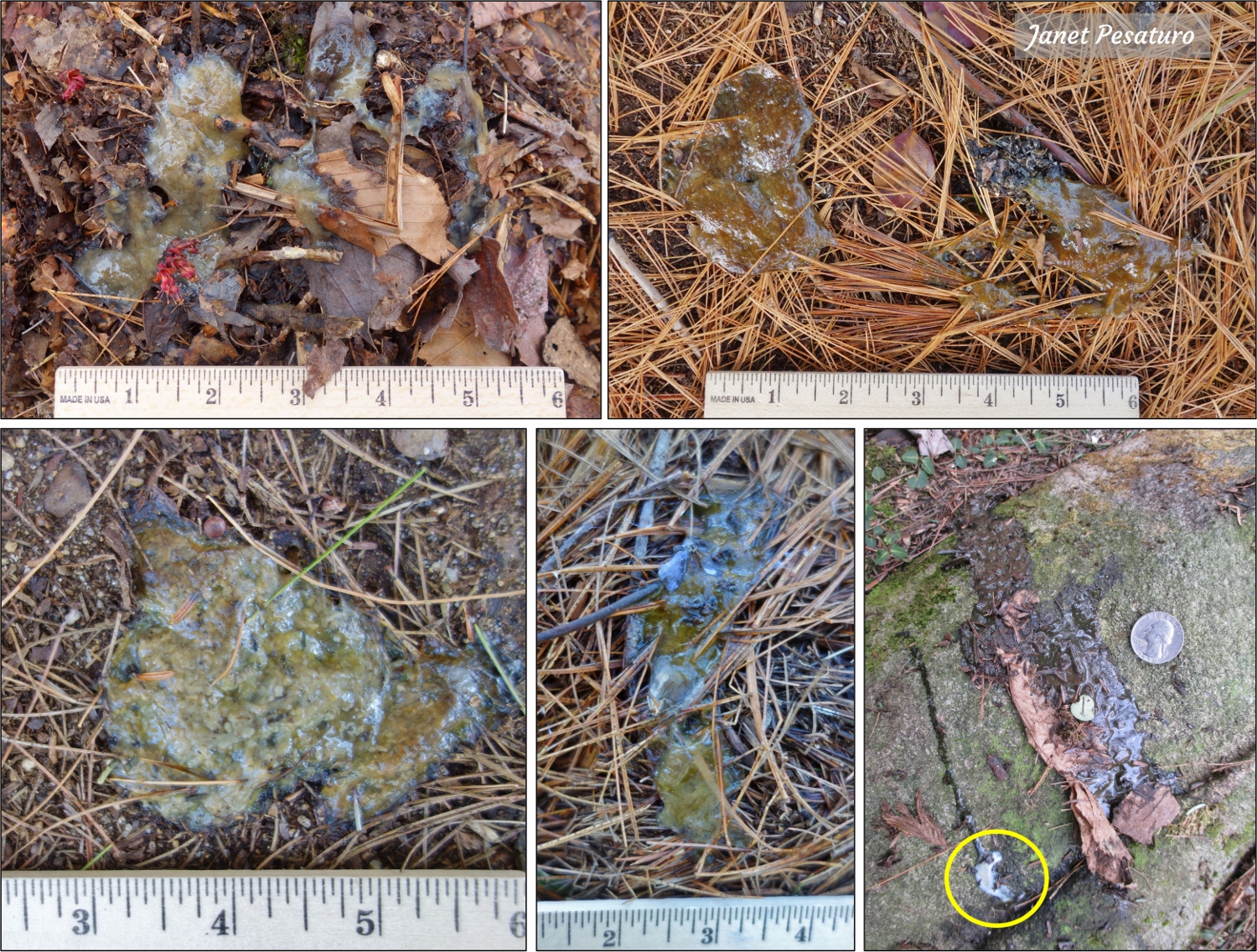

2. Otter Jelly and Anal Gland Secretions

I’m not sure otter biologists are all in agreement on the origin of these substances sometimes found in otter latrines, but I believe the yellowish brown material is intestinal mucus. I have seen it numerous times at freshly used latrines but because it’s just mucus it disappears rather soon after it dries, unlike the scats which contain fish scales or crayfish parts that persist for a long time after the scat dries up.

The other material, a whitish goo circled in yellow in the bottom right photo below, may be anal gland secretion. Or maybe it’s just another example of intestinal mucus; I’m not sure. In any case, I don’t think I’ve seen anything quite like it beyond this one time that I photographed it.

3. Otter Scent Mounds

Otters often create scent mounds by raking up material on the ground with their front feet. Mound making is a rather messy, rapid business as you will see in the videos at the end of this post. After raking up some debris, the otter then turns around and deposits scat, urine, and/or other secretions onto the mound.

The appearance of the mound depends on the available material on the ground – leaf litter, pine needles, sand, snow, etc. If there is a lot of loose debris on the ground, the scent mound can be well-formed and obvious. However, they don’t grow very tall because otters don’t usually keep adding to the same mounds in future visits. They may simply defecate on an existing mound or they may make new mounds with each visit, sometimes flattening out old ones as they roll around. Even when otter scent mounds are large and obvious, they have a rather loose, messy appearance, relative to beaver scent mounds, as you will see below.

4. Existing Elevated Surfaces

Sometimes, instead of creating a scent mound, an otter places its scat on an existing elevated object, such as a stump, rock, or beaver scent mound. Beaver scent mounds can be distinguished from otter scent mounds by noting that the former are composed of blackened mud and debris that beavers dredge up from the floor of the pond. They tend to be rather densely packed, as well, because beavers often add to the same mound in subsequent visits, in a careful, deliberate manner. See this article for photos of beaver scent mounds and a video of a beaver constructing an unusually large one.

The Latrine as a Whole

1. Overall appearance

Because otter latrines are used repeatedly (by definition) there is an accumulation of scats of different ages and usually multiple scent mounds. The scraping and rolling, which are part of the latrine routine, often create flattened or bare areas as well. Study the photos below for those features.

2. Size

I find it hard to measure the size of an otter latrine because sometimes the animals stop using one area and begin using another spot just a few feet away. Then the next season they may use yet another area a few feet away from the last. The following year, they may return to the first one…and so on. So is the latrine the entire area used in recent years, or just the area used this season? In the narrowest sense, an otter latrine can be as small as about 4 square feet.

3. Terminology and uncertainties

Further, sometimes current use includes multiple latrines connected by runs. Should we consider those to be multiple latrines, or is entire complex of latrines and runs one big latrine? I think “latrine” is too narrow a term for such a complex and will discuss this more in the Video section below.

Videos from Different Types of Latrine Sites

For me it’s easier to find and identify animal sign in the field if I have actually seen videos of the animal in action. It helps me read the landscape and visualize what, how, and where animals may be doing their thing. Sometimes videos even cause me to question current beliefs or ways of thinking about animals. Regarding otters, I’ve come to wonder if the concept of otter latrine as used in publications is too narrow. Read on and watch the videos to see why.

1. At a beaver bank lodge

An active beaver bank lodge is often a happening place because the beavers, of course, are maintaining it, and other species may use it as a lookout or scent post. Occasionally muskrats, otters, or mink co-habitate with beavers inside the lodge, though perhaps in separate chambers and not really intermingling with the beavers. However, it’s probably much more common that otters are using the outside of the lodge rather than the inside, while beavers occupy it.

On and around this lodge were clusters of otter scats and scent mounds. There were runs through the grass between latrine areas, and some flattened areas that might have been beds. Indeed, the video shows the otters using the area for resting and eating, as well as the usual latrine activities. So is each cluster of otter scent mounds a separate latrine, or is the entire area one large latrine? Or, should we think of this as something more than just a latrine? Is the area better understood as an otter home site or home base?

2. On a trail connecting two water bodies

The next video was captured by a camera that targets an animal trail that connects two ponds. The trail is only about 50 feet long. As the video shows, a variety of species use the trail, and otters have a latrine on it. There’s another otter latrine less than 100 feet away on the shore of one of the ponds, and yet another on a second trail that connects the ponds. Are these separate latrines, or is this better understood as one large latrine, or 3 latrines as part of a larger otter home site between the two ponds?

3. At a pond edge near a beaver dam

Below is another example of otter activity at one of several neighboring latrines connected by runs. Because of the lay of the land and position of the trees, we can’t place the camera in a way that gives the larger view, but I do wonder if the otters are using the whole area as more of a home site than just a cluster of toilets.

Sources

Newman, D. G. and C. R. Griffin. “Wetland Use by River Otters in Massachusetts.” The Journal of Wildlife Management. 58 (1994): 18-23.

Swimley, T. J., T. L. Serfass, R. P. Brooks and W. M. Tzilkowski. “Predicting Otter Latrine Sites in Pennsylvania.” Wildlife Society Bulletin. 26 (1998): 836-845.

Related Posts

- River Otter Scent Marking

- River Otter Toilet Training

- Gastroliths in Otter Scat

- River Otter Vocalizations

Please share your own observations, thoughts, and questions about otter latrines in a comment below.

Great videos, I certainly will look at otter latrine sites more thoughtfully. Learning so much more about otters behavior watching your videos. The videos are helping me to “read”the otter tracks I find and leading to a better understanding of what the otters are doing to make these tracks.Thank you, your videos are fascinating!

Helene

Great to hear. I have found videos hugely helpful in tracking. With tracking alone I just felt we were guessing, assuming, and missing too much.

Absolutely fascinating! I could sit and watch these all day long. I know more now than I did when I woke up this morning!

I’m glad you found it useful!

Janet,

A few years ago I captured a video that shows an otter vomiting up a yellow secretion that could explain some of the the otter jelly as well.

Ah, great point. I had forgotten about that but now recall you posting about it. Did you get a photo of the vomit, or do you recall if it looked like the otter “jelly” in my photos?

Janet,

Regards latrine sites that are relatively bare.

“The Latrine as a Whole

1. Overall appearance

Because otter latrines are used repeatedly (by definition) there is an accumulation of scats of different ages and usually multiple scent mounds. The scraping and rolling, which are part of the latrine routine, often create flattened or bare areas as well. Study the photos below for those features.”

I believe high concentrations of nitrogen in the scat, continually deposited in the same area influences plant growth and regeneration which also leads to these areas being bare.

I have noted this with both otters and black bears in my area. Black bears that feed almost exclusively on salmon in the late summer and fall deposit scats that will ‘burn’ the moss or grass they are deposited on. The scats result in a small area in the moss/grass that turn a light tan.

Some otter latrines I cam are nearly devoid of plant life. This ends up making for a nice cam site as brush and grass that cause wind triggers are sparce.

Great info – thanks. We see a lot of flattening of vegetation here but sometimes also a little brown-out which probably is due to the high nitrogen content of the scat, as you say. But there’s enough veg so that I almost always have to trim; sometimes a lot. The latrines in all 3 videos above required significant trimming. Are you dealing with coastal otters? If so, latrines may see heavier use because coastal otters travel in larger groups and latrines are used by multiple groups, or so I have read, and heavier use would mean more brown-out.

Amazing stuff, as usual

Thank you, Zobert

-Jane Pizzorato 😉

Janet, thank you for sharing so much great info on otters. My local conservation group – here on Cape Cod – are thinking of doing a study of local river otters. I assume these would be what you call “coastal” river otters. Could you suggest readings or other sources of information about coastal otters?

Hi Andrea, I don’t know of any good books or articles specific to coastal river otters, but Hans Kruuk’s book, Otters: Ecology, Behavior and Conservation, is an excellent in depth book about the natural history of various otter species around the world. You could also try contacting Mike Bottini, a wildlife biologist at Seatuck Environmental Association. He studies otters on Long Island which involves both inland and coastal populations, I believe.

This is great information! I have shared the link to this document when I have posted clips of these behaviors on the Minnesota Naturalists Facebook group.

I’m so glad it was useful! We have a lot of otters around here, so lots of opportunity to study them.

This was very helpful! We used to pick up shrimp the night before we planned to go fishing in coastal rivers and leave them in the bait bucket on the boat. We stopped because we kept finding scat on the boat in the morning. I thought it was raccoon but after seeing an otter nearby I searched and landed here. Definitely otter poop! He never got our shrimp but we got tired of cleaning up after him

Haha, you are lucky it was not a raccoon. A raccoon would have gotten into the bucket! Glad this post was helpful.